Mixed farmer George Young shares his thoughts on GM, and why he thinks it’s not the answer to human-created problems in the food system…

In Boris Johnson’s inaugural prime-ministerial speech, the most visible and concerning red flag he voiced was a push for genetic modification (GM) to be used in UK agriculture.

This has reignited the debate amongst farmers, with a recent Twitter poll from @aliceinwellies showing that 77% of farmers (based on 755 votes) would want to use GM “technology” on their farms if it were available. That’s a whole lot of people. And a statistic that I find very worrying.

So what are the reasons necessitating GM?

Disease resistance is a major one, as too is insect tolerance / resistance. Most folk appear to be against any herbicide associated with GM (from the valuable lessons learned from Roundup-ready crops – crops bred to be resistant to glyphosate, enabling glyphosate to be used to kill all the weeds growing up with the crop).

And the final reason touted for a thumbs up to GM is drought tolerance.

Unfortunately, the only valid issue here is drought tolerance, in order to mitigate the deleterious effects of climate change on our current cropping. But I don’t even believe that that is necessary. Let me explain…

The limits of ‘science’

From a Governmental and societal point of view, science is consistently touted as the be all and end all for judging whether or not something should be done.

Science will tell us if we are doing wrong or right. Science will inform us how to improve what we are doing. But science is much more limited that people realise.

Science is heavily based on statistics, which as everybody knows, can very easily be manipulated to skew and favour various points of view. And science only ever works with very limited variables; often one or two. I work with hundreds of variables on my farm.

Science in the mid-20th century was telling farmers to use a fantastic array of artificial fertilisers and pesticides (both of which incidentally have a massive carbon cost associated with them).

Yet here we are, 70-80 years later, with a gigantic wealth of agronomic issues stemming from the scientifically-based, agricultural ‘Green Revolution’ (I’m pretty sure this will be renamed at some point in our future).

Okay, we did produce more calories from the land, and the process of creating those calories was much simpler and systemic than it had been possible to be before.

But what we have managed to do is create nutritionally empty calories. In fact, we now need to consume twice the calories than we did 60 years ago for the same nutritional content. There is a reason there are so many overweight people putting strain (pun intended) on the heath system.

Have we forgotten Nature?

This science-based revolution led, additionally, to fields growing in size as hedgerows were ripped out and the desertification of much of the British countryside.

Why should we be providing habitat for ecology? Farms are food-production sites. And science has given us the means to grow our crops without Nature being involved. Who needs Nature?

This approach to agriculture is thoroughly breaking down now (possibly already broken). Fungicides are rightfully being revoked for their issues related to human health (I don’t believe their effect on soil life is cited as a reason, but it should be).

Many herbicides have also already been revoked, and resistance is growing on the entire list of active ingredients in weed-killers (I’m not going to mention the glyphosate argument here). Insecticides don’t work on target species any longer – but golly they do a great job on ladybirds and other beneficials.

So, in order to keep within this simple way of farming, with minimal labour on the land, the answer is obviously GM.

GM to simply create resistance to disease and pests in our crop, plus better natural scavenging for fertility in the soil. Done. Sorted. Science has come up trumps and done it again.

Crumbs. I think I have convinced myself. Or not…

Fixing our approach

What GM is doing here is trying to fix a bad approach to agriculture that governments all around the world have pushed since the end of WWII.

Instead of going back to basics and understanding how we are doing things wrong the whole time, we are trying to enable an incorrect (and un-ecological) approach to farming to continue. And we think it necessary because we are constantly told that we must feed the world.

The myth of ‘feeding the world’

Feeding the world is another myth that governments are happy to spin. There is a direct correlation between civil unrest and food prices. So unsurprisingly politicians want to keep food prices down. Which is done by over-supply.

Farmers should be able to achieve a lot more money for the food that is produced: We wouldn’t have to produce so many empty calories, and could instead go back to producing nutritional calories.

On a side note, owning a farm doesn’t give you the right to make a living from farming. Farming is a business – if you are good at that business you will succeed. If you aren’t, then you will go bust. Why should we expect support payments to support some of us being bad business-people?

Instead, the good business-people would have the opportunity to take over those other areas of land, or maybe we could actually get a plethora of new entrants into farming, with fresh, bright, new ideas to push the industry forward. Rather than uninspired ideas like GM crops.

Towards a new vision

Let me lay out my vision of what farming should look like: A non-systemic approach, something more akin to an art.

We all know that we need to plant more trees. Well, this is a bit of a shocking revelation, but trees also produce food. And there is a pretty magical way that trees can be used. It’s called agroforestry, where you still get to grow arable crops, but up the alleys in-between the rows of trees.

So why is this cool? You have just lost about 20% of your field area – that seems silly. But not only does that tree area harvest (in the form of fruit, nuts, coppice wood for furniture and energy), it also provides a beautiful habitat for beneficial insects and animals to flourish, and remove the desertification in the middle of our arable fields.

What’s more, the trees act as a barrier to prevent the carry of air-borne disease. Other methods to mitigate disease and insect pressure include planting populations (rather than mono-culture crops).

This may be populations within the same family – such as the Wakelyns population wheat – but could also be polycropping, with two or more unrelated species of plant grown together.

And the final thing: Maybe we could be growing a greater variety of crops. Is it a surprise that issues occur when cropping is a mix between cereals, rape, beans and peas? Could these other crops be livestock also? Mixed farming is pretty spectacular for the environment and ecology on farms, when done correctly.

Reconnecting with land and food

As I say though, this is a non-systemic, artistic approach to farming; one which requires vigilance on the land. And maybe a smaller farm, with more people working on it, to be successful.

Of course I am being naïve here again: We don’t want more people working on the land, understanding the value of food, where it comes from, and how difficult it is to grow. It is much better for farmers if people think that food comes from the supermarket. Much better that it only requires one man per 2,000ha to farm. GM enables this. GM is the answer.

Except it isn’t. So many societal and cultural problems exist due to our disconnect with food; something that GM will only enable to get worse.

There is one aspect of GM benefit that I have yet to address; drought/heat tolerance. Facetiousness aside, I agree, this could be a useful one. But still something that I don’t actually think is necessary.

For a start, I have been to farms in the middle of Australian summer (@hollandstrackfarm) where cover crops were being used to actually reduce the temperature within fields, essentially getting rid of the peaks and troughs of climate extremes.

This has the benefit of creating a more hospitable environment for ecology too. Trees also have effects such as this, and of course make a big difference when it comes to wind – just speak to Stephen Briggs.

Examining our diets

But if this isn’t enough, before we go down the GM route, might I suggest that we could also change our diet. We should be eating food that the land around us is capable of producing. If it can no longer produce wheat, that isn’t a problem. It is time for our diet to change and move away from bread and pasta.

The hidden side effects of GM are absolutely unknown. Unfortunately, humans have been constantly told to think that they know best (and consistently shown to be wrong about that, when it comes to Nature).

I heard a story of a GM pulse crop grown on a field-scale in Australia, its GM characteristic being immunity to a certain type of problem-insect that would feed on its sap. The sap in the GM plant would poison the insect, and the plant survive.

The issue is that, years later, the residue of that crop could still have failed to decompose. GM trials will be full of issues such as this. And perhaps some of the issues we won’t realise for 50-100 years, when our world will be in an even worse state than it is now.

Farmers – use your ‘arsenal’

I’m pretty certain this article will have changed few minds. Those who agree with me with nod vehemently. Those who disagree will pick holes, some of which I’m sure will hold validity (and plenty of which won’t).

I can say with certainly that GM won’t ever be grown on land owned by me. But I just implore farmers to think outside the box. And use the one tool in your arsenal that always has your back, and never charges for its services. NATURE.

*George Young is a mixed farmer in Essex, England, growing both conventional and niche organic crops, as well as raising beef cattle. He has a passion for ecology and education and wants to move away from ‘farming’ towards ‘food production’. He practices zero-till and once appeared on a TV show called ‘First Dates Hotel’.

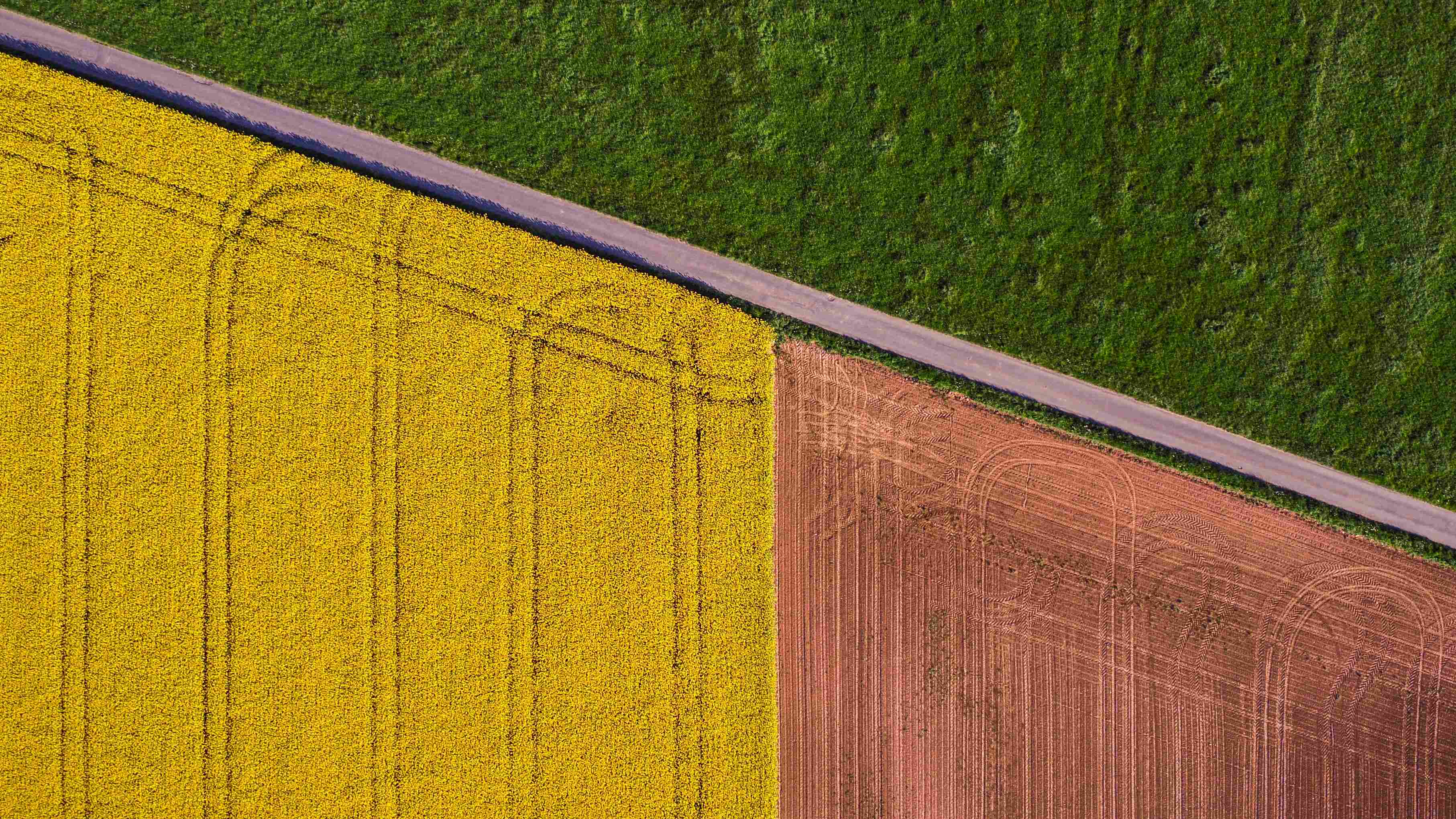

*Photo by jean wimmerlin on Unsplash