We need to get real, accept change, and find a ‘new normal’, says Rob at Rosewood Farm.

Climate change has been at the top of the agenda recently. With the Extinction Rebellion protests in London, and the school climate strikes happening across the globe, and now David Attenborough getting in on the act with ‘The Facts about Climate Change’, we know something will happen, as it did with plastic awareness.

I know when climate change is being discussed because, as a cattle grazier, I find that the hateful messages on social media tend to reach their peak. Some people, often with very anonymous SM accounts, feel justified in lambasting me for not caring or, as was the case this week, denying that climate change is happening.

So it’s time to set the record straight.

I, like most people who work on the land, either as farmers or in the conservation sector, am acutely aware the changing climate: We’re seeing it happening before our very eyes as it’s affecting the land and the weather, making our job more challenging.

However, rather than being late to the party, I can’t help but feel that I’ve been here for so long that I’m now trying to clear away glasses and straighten out the furniture.

It’s not so much that I think climate change won’t happen, but that we’re already about 200 years too late to avert ‘disaster’. I’m sure, if we’d realised in 1819, or 1719, what we were doing to the planet then we would have been able to avoid a 2 degree rise in temperatures by leaving fossil fuels where they were, and stopping the drainage of our wetlands, but we didn’t. And even that wouldn’t have prevented climate change.

I say this because the climate has always been changing, and no where are we more aware of this than in the Yorkshire Ings. Our grazing sites in the Ings were once at the bottom of the gigantic ‘Lake Humber’, formed when ice sheets in the Humber Estuary blocked the meltwater from the last ice age – we owe our landscape to climate change.

I don’t say this to give anyone an excuse to wreck our planet, merely to point out how insignificant we really are. Many of us see ourselves as ‘saving the planet’ but in reality the planet would be fine without us. Rather than being altruistic by addressing climate change, we are really seeking to maintain our own future on this wonderous ball of spinning rock.

Whenever I moot the suggestion that the natural world doesn’t need us, suddenly people who have decried humans as being a blot on this planet join forces with the most intensive of agvocates to condemn the idea, trying to derail the conversation by making out that I’ve advocated culling and/or starving people.

The same thing happens when I suggest that extensive beef production has a part to play in food production – the most intensive of farmers and plant-based advocates reveal that their concern for the natural world remains secondary to the belief that we can, and should, put the human species, and every one of us alive today above all other life on the planet.

The uncomfortable reality is that we aren’t unique as a species – despite our penchant for being hugely creative, we balance this with an ability to be equally destructive.

We need to talk about population

The basic premise that our society works towards, is that we need to maintain a growing (human) population and alter our resource use to enable this, whilst simultaneously reducing our numbers through birth control.

But in actual fact, the human species responds to improved food production by growing the population. This theory is too often rejected in favour of the belief that we remain in control of our food supply and produce more food in response to more people.

The only reason to perpetuate this myth is to maintain our feeling of superiority over other species that don’t farm, but in reality we remain as vulnerable as any other.

And what if the same could be said for the climate and associated sea level rises? Perhaps we have enjoyed a brief moment in time when sea levels allowed us to reclaim and drain land from the fertile wetlands in the east of England.

As little as 6,000 years ago, humans were pushed away from the rich landmass called ‘Doggerland’, which connected Great Britain to continental Europe, and a great area of wetland was lost to the melting ice sheets as it became the bed of the southern North Sea.

The Yorkshire Ings is well known for it’s low lying floodplain meadows that provide vital habitat to some of England’s rarest flora and fauna, but our neighbouring catchment, that of the River Foulness, is barely noticeable in the modern landscape.

Nearby place names such as ‘Water End’ and ‘Runner End’ suggest the extent of the floodplain that once was. Perhaps this is because ‘Foulness’, meaning dirty water, is rather less attractive than the Derwent, derived from the “valley thick with oaks”, which may have enhanced it’s preservation throughout time.

Today the Foulness is little more than a large drainage ditch serving the surrounding arable land. It was during drainage works by the Foulness, in 1984, at Hasholme Hall, that revealed a little more about how the area looked in the past.

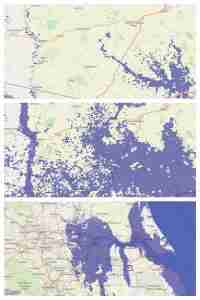

data taken from: flood.firetree.net/

In the late Iron Age, the river was still a tidal inlet of the River Humber and the discovery at Hasholme showed that it was capable of accommodating a 40-foot solid oak log boat with a significant cargo.

So what does this mean for the future of our landscape with climate change?

Well firstly, man-made climate change is definitely happening, there’s no denying that, but I think there are rather a lot of people out there who think that if we just stop driving cars and eating animals, then climate change will be stopped in it’s tracks and the human population saved.

Humans are a very adaptable species though, and although I’d agree that our vulnerability stems from our unwillingness to change, I doubt that our resistance to pre-emptively changing our diets is the biggest threat.

What worries me more is our willingness to reject tried and tested skills and technologies based upon their inability to sustain an increasing population, and adapt little by placing all our hopes on further intensification of our food production.

As the most telling discovery from the Hasholme boat, it’s cargo, shows:

The landscape around the Foulness is now home to a significant proportion of our vegetable production in East Yorkshire. Glasshouses are a key feature of the modern farming landscape, and most of our best vegetable growing land lies alongside the banks of the River Humber, at or below current sea levels, reclaimed from wetland and saltmarsh in our attempt to control nature.

The popular narrative goes that forest in the UK was originally cleared for pasture, but here the forest was flooded by rising sea levels and only became dry enough to grow crops again with extensive artificial drainage.

Cattle are now a rarity in the Foulness valley, as are trees, but the archaeological evidence suggests that both were important features of the landscape in Iron Age Britain. Oak, alder and hazel woodlands, alongside meadows and marshes, were a key feature of the landscape – much like the Ings to this day.

There’s little doubt that our climate is changing and some may see my steadfast commitment to the cow in our agricultural landscape as a snub to efforts to reverse this.

However I don’t think the future is looking too good for the human species if we continue to rely upon low level ex-marsh for our cultivated crops. Is it even sustainable to resist the natural rewetting of the land?

The humble cow has served us well in many climates throughout time and to reject them now, at this crucial point in human history, would seem to be a folly from which we could not recover.

We need a ‘new normal’

We need to accept change in all aspects of our lives and be ready to adapt to a new normal.

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach in such a rich and diverse world as ours. We have become complacent that our man made environment is ‘natural’ and ‘safe’ when in fact we have been living on borrowed land for some time.

Wetlands are not the barren wastelands to be drained and ‘improved’, and humans can continue to live sustainably within them. They provide us with food, fuel and transport, but if we are going to survive we need to seriously consider many new (and old) ways to tackle the impending crisis’.

Let’s really push the boat out, in more ways than one.