There is a good variety of defence systems employed by the flora of the British countryside. The steel like barbs of blackthorn, the snagging, scratching canes of brambles and the bitter taste of a dandelion that no doubt dissuades a grazing herbivore from gobbling it up.

And also prevents a small human from eating with his hands for the rest of the day having handled the plant. There’s one species that rises above its peers in the world of vegetation that can hold their own. Urtica dioica, the stinging nettle is the plant that commands a begrudging respect, from me at least.

I was fortunate to grow up in a home with a reasonably sized garden, in which my siblings and I played war games, went on adventures and recreated the major sporting events of the time amongst the domestic and wild plants that grew there.

The most significant danger was a seasonal one, when in late summer if you picked up a windfall apple to Henman-esque serve an ace at your unaware brother, there was a very strong chance that the other side of the apple was a buzzing mass of wasps.

But this danger was short lived compared to the almost constant threat of the nettle. The regular occurrence of an inaccurate drop-kick attempt of a flat Umbro football usually resulted in a rescue mission foray into the nettle infested ditch below the hedge that bordered the lawn.

Wearing shorts and armed with a bamboo cane pinched from the veg patch, it was normally successful but always came at a cost. The ankle bone, when wearing a trainer sock is a classic target for a nettle sting (incidentally, also one the worst place to be hit with a hockey ball on a cold day).

Even less pleasurable is the inner bicep, often targeted by a well grown nettle which you have unsuccessfully tried to raise your arms above like a Royal Marine wading in a jungle river.

I do think, however, the worst place to be stung by a nettle is the back of the knee. The thin skin that is constantly moving and maybe a little sweaty on a summer afternoon. You can rub the rash with dock leaf until that green tinge appears, but the irritation will last all day.

After all that, imagine my surprise when I learnt that people actually eat nettles. I have little real knowledge on the subject, but I assume that the nettle soups and teas of this world are solely consumed by sandal wearing off-grid hippies who survive on fair trade cous-cous and foraged weeds. But there is another way. And yes, it is cheese.

The Yarg

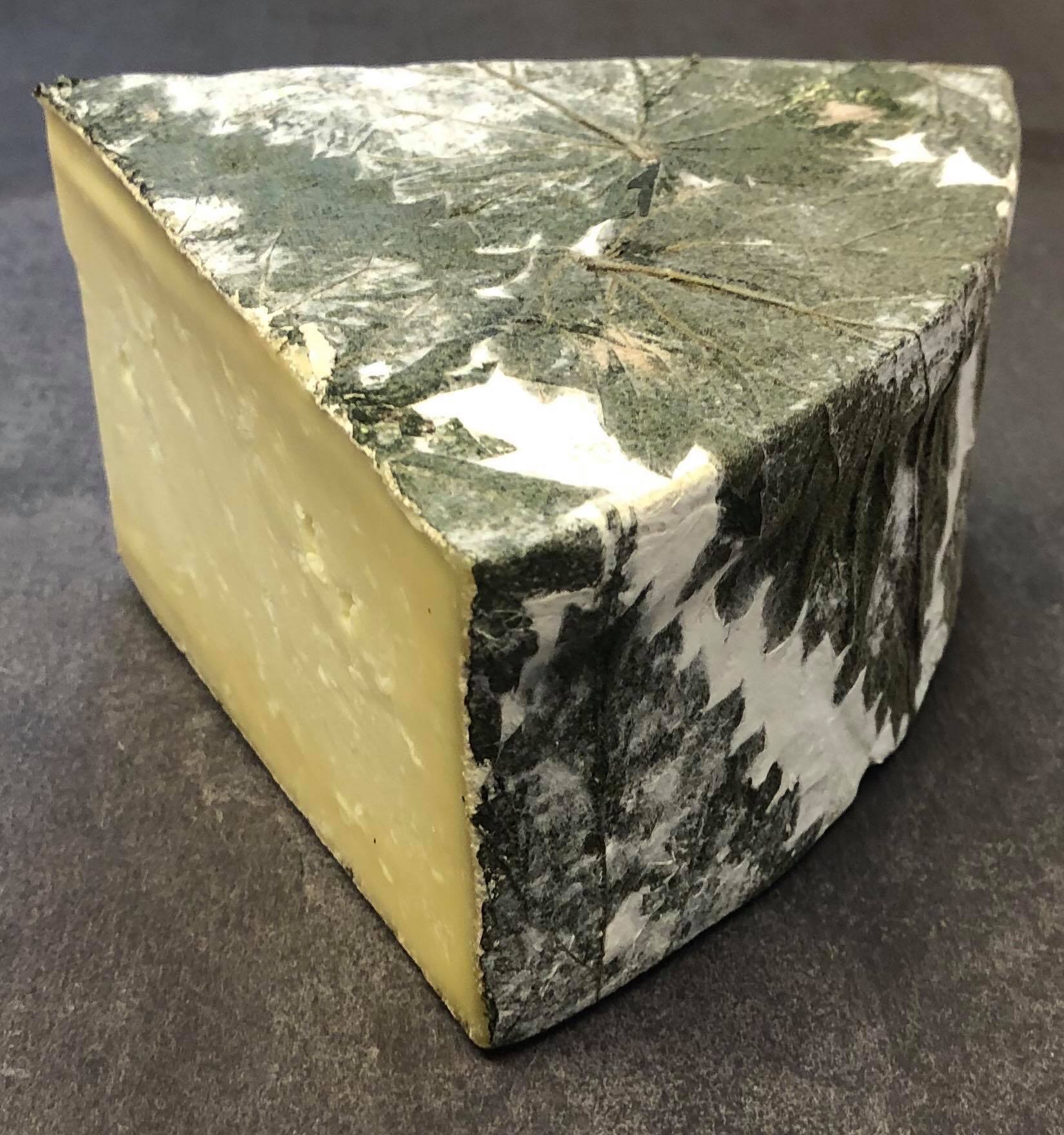

Cornish Yarg, made by Lynher Dairies near Truro, is wrapped in the leaves of the stinging nettle. It’s a great USP, more than a gimmick and adds a lot to the cheese.

The distinctive pattern of greenery on the rind is an attractive look, rustic winteriness as if the spring leaves have been frozen in time but on cheese.

The nettles add a surprisingly delicate herbaceous flavour to the semi hard white cheese especially given its name which sounds like the first word spoken by early Homo Erectus in a cave under Bodmin Moor.

In fact Yarg holds the name of its original creator spelled backwards, maybe inspired by that chap Robert who invented extra strong mints.

This cheese holds the balance well between self-supporting and crumbly, it slices well and breaks up nicely into fresh creamy fragments that I ate plenty of, directly from the cheeseboard.

It’s a great addition to the strong dairy tradition of the county of Cornwall and should be welcomed to your fridge shelf or your slate-shelved cheese cellar. It stands out on the board and in taste holds its own amongst more mature and punchy cheeses.

On the star scale of embarrassing wordplay Cornish Yarg is a ☆☆☆☆ ‘goud-a’ cheese.

☆ Camem-bare it

☆☆ Cheesed off

☆☆☆ Aver-aged

☆☆☆☆ Goud-a

☆☆☆☆☆ Un-brie-lievable

Again, I apologise. My regret is eternal.